Utopia, a dream and an illusion

With Wikipedia

eople are fascinated by the idea, that there could be a society or community, where everything is perfect or nearing perfection, where everybody is happy and fear and insecurity are absent. There have been many attempts to write about about such a society, and develop a social utopia model, but many of these turned out to describe an dystopian one. To actually develop of found such an utopian ideal as a physical community is an age-old endeavor. Not only as a physical place, but as an organization like in freemasonry or as a virtual space. The notion of cyberspace, a technological utopia imagined by Sci-fi writers and realized with digital technology was an utopia, which turned out to bring many goods, but also may threats to humanity.

In thinking about communities that at least in some respect would be better, more humane, more ecological we can therefore learn from the utopists, those who made intellectual or artistic constructs and those who actually tried to create an utopian or eutopian (mini-)society or community.

Why is the concept of Utopia relevant to community living or intentional communities? One could easily discard the whole notion of an Utopian society as a unrealistic, non dynamic dream of some writers, do-gooders or religious leaders, who believe that an ideal state or society could work but assume ideal people.

The actual communities that emerged, based on the various social utopian models turn out to become an exclusionary space, a space that is ideal for an elite and privileged section of society, the ones that "deserve"being part of it. Conform or leave, no middle way and don't think for yourselves, that's a sin or a crime.

Some communities did survive and prosper, most didn't. It is easy to point out how the human limitations like ego and material greed could make such an aspiring utopian society or community a pipe-dream, a fata-morgana, an illusion that could never work. And yet, most of us strive to improve our lives and our part of the world, from a selfish or social point of view, we vote for those who promise us those improvements,

We like to believe in a solution, a promising perspective, especially when in dire straits, when problems arise that go beyond individual competence and agency. In most political movements and even in the narrative concerning Corona there was this utopian perspective of science,of progress and the vaccines that would save us all. There is a distinct utopian flavor in scientific thinking, most scientists believe in progress, in some kind of teleological perspective that we can manage this world and society towards a better future.

We all have dreams about a world that would be more perfect, better organized, less greedy, more humane that what we experience in our daily life. And even those who believe that there is sense and direction in what we perceive as reality, that our world is a great school with a perfect curriculum at times are tempted to change that a bit, make it a better place for all of us. These dreams, all through history, have been laid down in books or verse, painted or sculpted in art and appear in the various interpretations of heaven, paradise. Many times these ideas or dreams were tested in reality, in communities, ashrams, monasteries, cults, in whole countries but alas, without much lasting success. Only monasteries and religious communities seem to have staying power and a sustainable model, but even there many were short-lived.

For those who are planning an intentional work/live/create community it does make sense to study the historical and conceptual aspects of the virtual and real utopia’s. One has to consider the limitations, no community will ever be a real and perfect utopia, as we cannot and don’t intend to separate from the rest of the world (even planetary relocation plans don't discard their origin on earth). Even a very spiritual endeavor will have no ambition to be more that an a little seed in the sea of awareness.

The Utopian concepts do have value for us, as their usually deal with one or more of the aspects of scarcity, be it material or the less defined needs for happiness or security.

One gets the impression, that the various utopist writers have usually projected some part of their own personality into their utopian worldview at the expense of a more balanced approach. Often practical aspects are neglected or just assumed like where the material affluence, overcoming the need to worry about food etc, Or like in P<$I[]Plato>lato’s or Skinner’s (Walden 2) ideal societies there are kings/philosophers or very gifted planner/executives who in fact establish a kind of totalitarian regime. The question is always who is controlling the controllers, who is planning the planners, and monitoring the feedback mechanisms. We know by now, that what we hoped for and assumed works (like in democracy) often fails or is missing. They assume an ideal state based on ideal people and a social understanding among them, but already Rous<$I[]Rousseau, Jean-Jaques>seau was realistic enough to admit that this is fictional, real people have real human shortcomings.

Another aspect that is missing in many utopia’s is the development of the individual, how to deal with frustrations, criminal intent, depressions etc. Again a the ideal human doesn’t have these problems so they are ignored or treated as a residue of the non-ideal past. But an real community does have to deal with this and organising war games as in Ecotopia is a kind of drastic solution. The inner development of the partners and guest of the community is, in my view, the most important, it really should be school for life, a place for growth, not a kind of material paradise where everybody lives long, happily but without change or development. This is missing in most utopian concepts.

So these are relevant questions:

. Is utopia possible?

. Are utopian ideas meant to be acted on?

. If not, what other purposes do they serve?

. What practical lessons can we learn?

. Is there a theoretical model that classifies utopian concepts?

. Are we able to imagine ourselves living in these worlds? What about individual will and desire?

. Are totalitarian and even fascist societies utopian?

.

The literature includes:

. Plato’s Republic. Plato (c.380 B.C.) proposes a classification of the society into a three-tier and fairly elitist rigid structure of “gold”, ”silver” and”bronze” people according to their socio-economic status.

. Manu (a religious leader in the millenium BC) as can be derived from Manusmriti (The Lawsof Manu), provided various ‘laws’ and a four-tier hierarchy for the proper functioning of the society.

. Utopia (Thomas Moore,1516) gave the name to the genre of describing a perfect imaginary world and defines a city by its title (Utopia) and sees it as totally run by its government. In "The City and the Machine: (Lewis Mumford, 1965) and "The Story of Utopias (1922) more practical guidelines are outlined.

There are many, many utopian visions like The Communist Manifesto (Marx and Engels, 1847) aiming at equality and ending class-distictions,

We can find the origins of utopian ideas in

images of perfection and imagined ideal societies from classical and biblical

literature. A tension between the ideal and the real can be felt in nearly all

of the sources. Many of these worlds are set outside history in a golden age,

before time began or in a mythical time governed by its own rules. The idea of

a Garden of Eden is a kind of utopian concept. The Genesis story of creation,

told in the opening chapter of the Bible, is one of the earliest descriptions

of paradise. The image of the Garden of Eden is a powerful one. The creation

myth and the Garden of Eden represent the beginning of human time and

experience, and therefore can conjure powerful images of a pure time and place,

unmarked by history. In common with other early myths, it is set outside time

and marks an ideal or Golden Age before things went wrong in the world.

The Genesis myth was set in

Plato was a

Greek philosopher who lived between 427 and 347 BC. Plato argues, notably in

The Republic, that wisdom based on truth and reason is at the heart of the just

person and the just society. One of the passages describes prisoners trapped in

a cave, watching shadows of life outside cast on the wall by the light of a

fire. After a while they will think of the shadows as reality. But in truth

reality is different and can only be known by those outside the cave who live

in the light of the sun. Plato describes his statesmen (guardians) as people

who have struggled to the sunlight of reason and learnt the truth about the

material world (physics) and the moral and spiritual world (metaphysics.) Only

such philosophers can be trusted to rule the state. The Republic (Greek: Πολιτεία

/ Politeía, meaning "political system;" Latin: Res Publica,

meaning "public business") is a Socratic dialogue, written in

approximately 360 BC. It is one of the most influential works of philosophy and

political theory, and arguably Plato's best known work. In it, Socrates and

various other Athenians and foreigners discuss the meaning of justice and

whether the just man is happier than the unjust man by constructing an

imaginary city ruled by philosopher-kings. The dialogue also discusses the

nature of the philosopher, Plato's Theory

of Forms, the conflict between philosophy and poetry, and the immortality

of the soul.

Aristotle's Politics

(Greek Πολιτικά) about how a city

(polis) is to be organized is a work of political philosophy and kind of models

many of Plato’s notions, sometimes with a different conclusions.

Virgil was a Roman poet (70-19 BC). Unlike the earlier writers who often described the Golden Age as outside time or virtual, Virgil's Eclogue suggests that human progress might lead to a more affluent and leisured world in the foreseeable future. His fourth Eclogue, the Messianic Eclogue, is the clearest example of the shift from a timeless to a more historical view of a perfect world. An eclogue is a 'pastoral' poem that idealizes rural life. The term messianic suggests the promise of rescue or relief.

The Amphictyons by Telecleides, a Greek comic poet of the 5th century BC, is quoted by Athenaus. Telecleides presents in The Deipnosophists a Golden Age of impossibly effortless plenty. He plays on his audience's understanding that this ideal era never truly existed and never would. By presenting one extreme satirically he implies a belief in the opposite idea - that prosperity is the result of hard work.

Utopia is a name for an ideal society, taken

from the title of a book written in 1516 by Sir

Thomas More describing a fictional island in the

The word comes from Greek: οὐ, "not", and

τόπος, "place", indicating that More was

utilizing the concept as allegory and did not consider such an ideal place to

be realistically possible. It is worth noting that the homophone Eutopia,

derived from the Greek εὖ, "good" or "well", and τόπος,

"place", signifies a double meaning that was almost certainly intended.

Despite this, most modern usage of the term "Utopia" assumes the

latter meaning, that of a place of perfection rather than nonexistence. Some

questions have arisen about the fact that writers and people in history have

used utopia to define a perfect place. Utopia is a perfect but unreal

place. A proper definition of a perfect and real place is eutopia.

More's utopia is largely

based on Plato's Republic.

It is a perfect version of Republic wherein the beauties of society

reign (eg: equality and a general pacifist

attitude), although its citizens are all ready to fight if need be. The evils

of society, eg: poverty and misery, are all removed. It has few laws, no lawyers and rarely

sends its citizens to war, but hires mercenaries from among its war-prone

neighbors (these mercenaries were deliberately sent into dangerous situations

in the hope that the more warlike populations of all surrounding countries will

be weeded out, leaving peaceful peoples). The society encourages tolerance of

all religions. Some readers have chosen to accept this imaginary society as the

realistic blueprint for a working nation, while others have postulated More

intended nothing of the sort. Some maintain the position that More's Utopia

functions only on the level of a satire, a work intended to reveal more about

the

Economic utopia

These utopias are based on

economics. Most intentional communities attempting to create an economic utopia

were formed in response to the harsh economic conditions of the 19th century.

Particularly in the early

nineteenth century, several utopian ideas arose, often in response to the

social disruption created by the development of commercialism

and capitalism.

These are often grouped in a greater "utopian

socialist" movement, due to their shared characteristics: an egalitarian

distribution of goods, frequently with the total abolition of money, and citizens

only doing work which they enjoy and which is for the common good,

leaving them with ample time for the cultivation of the arts and sciences. One

classic example of such a utopia was Edward

Bellamy's Looking Backward. Another socialist utopia is William

Morris' News from Nowhere, written partially in

response to the top-down (bureaucratic) nature of Bellamy's utopia, which Morris

criticized. However, as the socialist movement developed it moved away from

utopianism; Marx in

particular became a harsh critic of earlier socialism he described as utopian.

(For more information see the History of Socialism article.) Also consider Eric Frank Russell's book The Great Explosion (1963) whose last section

details an economic and social utopia. This forms the first mention of the idea

of Local Exchange Trading Systems

(LETS).

Utopias have also been imagined

by the opposite side of the political spectrum. For example, Robert A. Heinlein's The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress

portrays an individualistic and libertarian

utopia. Capitalist

utopias of this sort are generally based on free market

economies, in which the presupposition is that private enterprise and personal

initiative without an institution of coercion, government,

provides the greatest opportunity for achievement and progress of both the

individual and society as a whole.

There is another view that

capitalist utopias do not address the issue of market

failure, any more than socialist utopias address the issue of planning

failure. Thus a blend of socialism and capitalism

is seen by some as the type of economy in a utopia. It talks about the idea of

small, community-owned enterprises working under the capitalist model of

economy.

Political

and historical utopia

Political utopias are ones in

which the government establishes a society that is striving toward perfection.

Rational thinking and a morality that was assumed should bring happines to all.

They tend to be static, totalitarian and lack a balance of power, the good

comes from above and cannot be criticized. But who controls the controllers, as

ideal or even holy leaders are rare. A global utopia of world peace is often

seen as one of the possible inevitable endings of history.

Island

Utopia’s

Many utopias are isolated societies, set on remote islands or planets, and discovered by outsiders.

Thomas Campanella imagined a perfect

society in which religion and reason work in total harmony. His La città

H G Wells described a parallel earth upon which the rational and scientific are perfectly reconciled with spiritual discipline and belief. Wells' Modern Utopia was first published in 1905. It set the scene for many modern, scientific utopias and dystopias. The story is set on a planet very like earth. The Utopian Planet differs from earth in that the inhabitants have created a perfect society. Two men, the narrator and his colleague (a botanist), visit this parallel planet and argue over its merits and defects.

Utopia is a world in which the problems of humanity have been solved. People live healthy, happy lives in cities where all human needs are met. Science and technology frees people from toil and enables them to enjoy security and innovation. Wells' utopia is neither democratic nor equal. He draws on the utopias of Plato, More, and Bacon. He advocates a scientific kind of socialism, rooted in the idea that the world is orderly, knowable and controllable.

The state is ruled by the Samurai. Like Plato's Guardians, the Samurai are a moral and spiritual ruling class. They lead an ascetic (disciplined and morally strict) life, governed by the Rule. The Samurai carry out their government duties but their main business is the development of science and philosophy. Anybody that proves themselves to be able to follow the Rule is allowed to become one of the Samurai.

In 1719 Daniel Defoe's story Robinson Crusoe explored the possibility of a solitary utopia.

Seven years later the poet, clergyman and satirist Jonathan Swift (1667-1745) published Gulliver's Travels - a satire on the society of the day and a warning about human folly.

Gulliver's Travels comprises four books. In each Lemuel Gulliver embarks on a voyage and is cast upon a strange land.

In the first book he becomes the giant prisoner of the six inch high Lilliputians. In the second he arrives in Brobdingnag -a land of giants. Book three takes Gulliver to Laputa, a floating island whose inhabitants are so preoccupied with higher speculations that they are in constant danger of collision.

In book four, Gulliver travels to the utopian island of the Houyhnhnms; grave and rational horses devoid of any passion, even sexual desire. The island is also inhabited by Yahoos - vicious and repulsive creatures used by the Houyhnhnms for menial work. Gulliver initially pretends not to recognize the Yahoos, but eventually admits that they are human beings.

Gulliver himself, and each of the populations encountered by him, can be identified with distinct aspects of contemporary society and human nature. Through encounters with a series of very different worlds, some of them the exact inverse of the other, Jonathan Swift exposes in Gulliver’s travels the inevitable prejudice and conflict within societies and between them.

Francis Bacon describes a remote utopian

island governed entirely by reason and science. Bacon's utopia, 'The New Atlantis'

was not published until after his death in 1627. He tells of the discovery of

the New Atlantis, a utopian island set beyond both the

Aldous Huxley in

Religious utopia

Rational or economic

concept are one way to get to a better world, but many utopias are based on religious ideals, and are to date those most commonly

found in human society. Their members are usually required to follow and

believe in the particular religious tradition that established the utopia. Some

permit non-believers or non-adherents to take up residence within them; others

(such as the Community at Qumran) do not. There have been many

religious communities with Utopian tendencies, from the Essenes to the Osho

communes.

New Harmony, a utopian attempt; formerly named

Harmony, was founded by the Harmony

Society, headed by George Rapp (also known as Johann Georg(e) Rapp) in

1814. This was the second of three towns built by the pietist, communal German

religious group, known as Harmonists, Harmonites or Rappites. The other two

towns founded by the Harmonites were Harmony, Pennsylvania (their first town),

and Economy, Pennsylvania (now called Ambridge, Pennsylvania) When the society

decided to move back to Pennsylvania around 1824, they sold the

Luddites (and neo-luddites) are

like the Amish, but more violent, they reject new technology and machines and

actually try to destroy it. The Luddites were a social movement of British textile

artisans in the early nineteenth century who protested – often by destroying

mechanized looms – against the changes produced by the Industrial Revolution,

which they felt threatened their livelihood. This English historical movement

has to be seen in its context of the harsh economic climate due to the

Napoleonic Wars; but since then, the term Luddite has been used to describe

anyone opposed to technological progress and technological change. The Luddite

movement, which began in 1811, took its name from the fictive Ned Ludd. For

a short time the movement was so strong that it clashed in battles with the

British Army. Measures taken by the government included a mass trial at York in 1812 that

resulted in many executions and penal transportation. The principal objection

was the introduction of new wide-framed looms that could be operated by cheap,

relatively unskilled labour, resulting in the loss of jobs for many textile

workers.

Neo-Luddism is a modern movement of opposition to

specific or general technological development. Few people describe themselves

as neo-Luddites (though it is common, certainly in the UK, for people to

self-deprecatingly describe themselves as Luddites if

they dislike or have difficulty using modern technology); the term

"neo-Luddite" is most often deployed by advocates of technology to

describe persons or organizations that resist technological advances.

Neo-Luddite thinkers usually reject the popular claim that technology is

essentially "value free" or "amoral", that it is merely a

set of tools which can be used for either good or evil. Instead, they argue

that certain technologies have an inherent tendency to reinforce or undermine

particular values. In particular, they argue that some technologies foster

social/class alienation, environmental degradation, and spiritual dissipation,

though they are always marketed as uniformly positive by the companies that

make them. Neo-Luddites claim that technology is a force that may do any or all

of the following: dehumanise and alienate people; destroy traditional cultures,

societies, and family structure; pollute languages; reduce the need for

person-to-person contact; alter the very definition of what it means to be

human; or damage the evolved life-support systems of the Earth's entire

biosphere so gravely as to cause human extinction.

The Islamic, Jewish, and Christian

ideas of the Garden of Eden and Heaven may be

interpreted as forms of utopianism, especially in their folk-religious

forms. Such religious "utopias" are often described as "gardens

of delight", implying an existence free from worry in a state of bliss or

enlightenment. They postulate existences free from sin, pain, poverty and

death, and often assume communion with beings such as angels or the houri. In a similar

sense the Hindu

concept of Moksha

and the Buddhist

concept of Nirvana

may be thought of as a kind of utopia. In Hinduism or Buddhism, however, utopia

is not a place but a state of mind. A belief that if we are able to practice

meditation without continuous stream of thoughts, we are able to reach

enlightenment. This enlightenment promises exit from the cycle of life and

death, relating back to the concept of utopia.

However, the usual idea of

Utopia, which is normally created by human effort, is more clearly evident in

the use of these ideas as the bases for religious utopias, as members

attempt to establish/reestablish on Earth a society which reflects the virtues

and values they believe have been lost or which await them in the Afterlife.

In the United States and Europe during the Second

Great Awakening of

the nineteenth century and thereafter, many radical religious groups formed

eutopian societies. They sought to form communities where all aspects of

people's lives could be governed by their faith. Among the best-known of these

eutopian societies was the Shaker movement, which originated in

See also: End of the world (religion), Eschatology, and Millennialism

Satirical

and Other Utopias

The adjective utopian

has come into some disrepute and is frequently used contemptuously to mean

impractical or impossibly visionary. The device of describing a utopia in

satire or for the exercise of wit is almost as old as the serious utopia. The satiric device goes back to such

comic utopias as that of Aristophanes in The Birds.

18th & 19th Century Methods

for change

In the 18th-century

Enlightenment, Jean Jacques Rousseau and others gave impetus to the belief that

an ideal society—a Golden Age—had existed in the primitive days of European

society before the development of civilization corrupted it. This faith in

natural order and the innate goodness of humanity had a strong influence on the

growth of visionary or utopian socialism. The end in view of these thinkers was

usually an idealistic communism based on economic self-sufficiency or on the

interaction of ideal communities. Saint-Simon, Étienne Cabet,

Charles Fourier,

and Pierre Joseph Proudhon in

The rationalists of the Enlightenment who

helped prepare the way for the revolutions of 1776 and 1789 did not produce any

recognized utopian classics. There were, however, utopian elements in

variousworks, suchas Fénelon's Adventures of Telemachus (1699), Montesquieu's Persian Letters (1721), the sketch of

Rationalism did bring a new view on utopia as a logical result of science and progress, somewhat like Virgil did. The change, that came about through the scientific revolution, has it counterpart in society. Revolution may be a movement of dramatic change, but it requires organisation. Change can also happen via diplomacy, dissent, representation, reform, petition and manifesto. In order to overturn or effect the existing order it is necessary to work to some degree within or upon the institutions and systems of that order.

The founding fathers of

In 1766

19th century Earthly Utopias

In the 19th century, at a time of massive

industrial growth, Robert Owen and Titus Salt, both industrialists and

reformers, set up model communities to house the workers at their textile

mills. These experimental communities are often referred to as socialist

utopias. Owen's New Lanark, in central

The backdrop to these small-scale social experiments was a growing emphasis on human rights, equality and democracy. The commentator Henry MacNab visited the Scottish Mill community of New Lanark and wrote a full account of Robert Owen's pioneering work on social welfare and community living in his book 'The New Views of Mr Owen of Lanark' (1819). He was particularly interested in Robert Owen's strict, but reformist approach to discipline. Owen adopted a carrot and stick approach. Employees could, for example, be dismissed for failing to turn up to work or for other offences which today would warrant a lesser punishment. His intention was to reward honesty and hard work as well as punish wrong doing. Drunkenness and deceitful behaviour were not tolerated.

Scientific and technological utopia

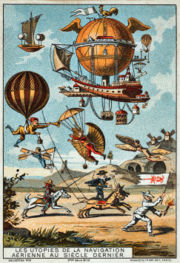

Utopian flying machines of the previous century, France, 1890-1900

(chromolithograph trading card).

Opposing this optimism is the prediction that advanced science and technology will, through deliberate misuse or accident, cause environmental damage or even humanity's extinction. Critics advocate precautions against the premature embrace of new technologies.

French Utopia’s

In France (neglecting an

isolated effort in 1616, the anonymous Huguenot Royaume d'Antangil), a

tradition of Utopian fiction developed during the early Enlightenment.

The pattern was fixed in the 1670s by the inventions of Foigny and Veiras, both set in the as-yet unexplored southern

continent. Tyssot de

Patot's ‘

More influential were works not strictly speaking Utopian, but containing

Utopian episodes, above all Fénelon's Télémaque, imitated by his disciple Ramsay (Voyages de Cyrus) and by Terrasson (Séthos). Montesquieu's

regenerated Troglodytes, in the Lettres persanes, and perhaps even the Eldoradans of

Candide, are also Fénelonian. The critical

potential of Utopia was also exploited: vigorously in La Hontan's idealized, anti-European Native

American society, more mildly in Marivaux's stage Utopia L' Île des esclaves, and with humour, as regards

religion and sex, in Diderot's Tahiti ( Supplément au

Voyage de Bougainville).

After 1750, as freedom of publication increased, political idealism was

expressed more overtly, in treatises rather than fiction. Morelly's Utopian epic,

Communism is the idea of a free society with no division or alienation, where mankind is free from oppression and scarcity. A communist society would have no governments, countries, or class divisions. In Marxism-Leninism, Socialism is the intermediate system between capitalism and communism, when the government is in the process of changing the means of ownership from privatism, to collective ownership. According to the Marxist argument for communism, the main characteristic of human life in class society is alienation; and communism is desirable because it entails the full realization of human freedom. Marx here follows Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel in conceiving freedom not merely as an absence of restraints but as action with content. In the popular slogan that was adopted by the communist movement, communism was a world in which each gave according to their abilities, and received according to their needs. The German Ideology (1845) was one of Marx's few writings to elaborate on the communist future:

"In communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic."

Following the proletariats' defeat of capitalism, a new classless society would emerge based on the idea: 'from each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs'. In such a society, land, industry, labour and wealth would be shared between all people. All people would have the right to an education, and class structures would disappear. Harmony would reign, and the state would simply 'wither away'.

New World

Order Utopia

Or just Utopia is a

movement newly formed in

1. We must do away with all

form of monetary funds; we are just supplying a service.

2. We must do away with

competition. Company A and Company B are making the same thing. There is simply

no point.

3. The issue of a practical

energy source. We need to develop other sources of energy in lieu of eventually

getting of this planet.

4. We should initially

refurbish housing of all to pleasing and acceptable standards then for every

family unit to inhabit equitable residences.

5. We develop a free

universal health care system.

6. The issue of the penal

system. Prisons need to be less cruel and inhumane.

7. Education is free.

8. Our world governments

shall dissolve under the above system concentrating a great extent on space

exploration in lieu of the fact that Earth will not last forever.

9. The above steps will

allow for an alleviated workload on ourselves meaning our times of labor will

be cut in half if we wish.

10. Lastly not least, the

above will allow us for more time to create a world of art.

Finding utopia

All these myths also

express some hope that the idyllic state of affairs they describe is

not irretrievably and irrevocably lost to mankind, that it can be regained in

some way or other.

One way would be to look

for the earthly paradise -- for a place like Shangri-La, hidden in the Tibetan mountains and described by James Hilton in his Utopian novel Lost Horizon (1933). Such paradise on earth must

be somewhere if only man were able to find it. Christopher Columbus followed directly in this tradition

in his belief that he had found the Garden of Eden when, towards the end of the 15th century, he

first encountered the New World and its peoples.

Another way of regaining

the lost paradise (or Paradise Lost, as 17th century English poet John Milton calls it) would be to wait for the future, for

the return of the Golden Age. According to Christian theology, man's Fall from Paradise, caused

by man alone when he disobeyed God ("but of the tree of the knowledge of

good and evil, thou shalt not eat of it"), has resulted in the wickedness

of character that all human beings have been born with since ("Original Sin") such as Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four became the primary method of

Utopian expression and rejection. (Kumar 1987)

Still, post-war era also

found some Utopianist fiction for some future harmonic state of humanity (e.g. Demolition Man (film)).

In a scientific approach to

finding utopia, The Global scenario group, an international group of

scientists founded by Paul Raskin, used scenario analysis and backcasting to map out a path to an environmentally

sustainable and socially equitable future. Its findings suggest that a global

citizens movement is necessary to steer political, economic, and corporate

entities toward this new sustainability paradigm.

Examples of

utopia

See also utopian and dystopian fiction

- Plato's Republic (400 BC) was, at least on one level, a description of a political

utopia ruled by an elite of philosopher kings, conceived by Plato. (Compare to his Laws, discussing laws for a real

city.)

- The City of God (written 413–426) by Augustine of Hippo, describes an

ideal city, the "eternal" Jerusalem, the archetype of all

Christian utopias.

- Utopia (1516) by Thomas More a Gutenberg text of the book

- Reipublicae Christianopolitanae descriptio

(Beschreibung des Staates Christenstadt) (1619) by Johann Valentin Andreæ, describes a

Christian utopia inhabited by a community of scholar-artisans and run as a

democracy.

- The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621) by Robert Burton, a utopian society is

described in the preface.

- The City of the Sun (1623) by Tommaso Campanella depicts a

theocratic and communist society.

- The New Atlantis (1627) by Francis Bacon.

- Zwaanendael Colony (1631) by Pieter Corneliszoon Plockhoy in Delaware.

- Walden by Thoreau

- Walden 2by B.F. Skinner

- News from Nowhere by William Morris (1892), "Pardon

me, Who strive to build a shadowy isle of bliss Midmost the beating of the

steely sea".[1] Shows "Nowhere", a

place without politics, a future society based on common ownership and

democratic control of the means of production.

- Gloriana,

or the Revolution of 1900 (1890) by Lady Florence Dixie. The female

protagonist poses as a man, Hector l'Estrange, is elected to the House of Commons, and wins women the vote. The book ends in

the year 1999, with a description of a prosperous and peaceful Britain

governed by women.[2]

- New Australia founded 1893

- H. G. Wells's A Modern Utopia (1905) is half

fiction and half philosophical debate.

- Aldous Huxley's Brave New World (1932), a

pseudo-utopian satire (see also dystopia).

- Shangri-La described in the novel Lost Horizon by James Hilton (1933)

- Islandia (1942), by Austin Tappan Wright, an imaginary

island in the Southern Hemisphere, a utopian containing many Arcadian elements, including a

rejection of technology.

- Hermann Hesse's The Glass Bead Game (1943) shows

Castalia, a utopian society for the intellectual elite.

- The Cloud of Magellan (1955) by Stanisław Lem

- Andromeda Nebula (1957) is a classic communist utopia by Ivan Efremov

- Island (novel) (1962) by Aldous Huxley follows the story of

Will Farnaby, a cynical journalist, who shipwrecks on the fictional island

of Pala and experiences their unique culture and traditions which create a

utopian society. Often considered his antithesis to Brave New World.

- The Great Explosion, Eric Frank Russell (1963) In the last

section setting out a workable utopian economic system leading to a

different social and political reality.

- The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas (1969), by Ursula K. Le Guin, about the costs of

utopia

- Ecotopia: The Notebooks and Reports

of William Weston (1975) by Ernest Callenbach, ecological utopia

in which the Pacific Northwest has seceded from the union to set up a new

society.

- Woman on the Edge of Time (1976) by Marge Piercy, the story of a

middle-aged Hispanic woman who has visions of a utopian society.

- The Probability Broach (1980), by L. Neil Smith, presents both utopian

and dysutopian views of present day North America, through alternative

outcomes of the American War for Independence.

- Always Coming Home (1985), by Ursula K. Le Guin, a combination of

fiction and fictional anthropology about a society in

California in the distant future

- The Hedonistic Imperative (1996), an online manifesto by David Pearce, outlines how genetic engineering and nanotechnology will abolish suffering in all sentient life.

- The Matrix (1999), a film by the Wachowski brothers, describes a virtual reality controlled by artificial intelligence such as Agent Smith. Smith says that the

first Matrix was a utopia, but humans rejected it because they

"define their reality through misery and suffering." Therefore,

the Matrix was redesigned to simulate human civilization with all its

suffering.

- K-PAX (2001), a

film based on the book of the same name, is about a man who calls himself

prot, an alien from a "utopian planet" K-PAX.

- Equilibrium (2002), a film about an utopia where all emotion is forbidden,

which is considered the only way to peace and balance.

- Globus Cassus (2004), is a project for the transformation of the Earth into a

large, hollow structure inhabited on the inside, which would be organised

by new types of societies and political systems.

- Lois Lowry's The Giver

- Doris Lessing's Shikasta, Memoirs of a Survivor

- Elisabeth Vonarburg's Reluctant

Voyagers (Les Voyageurs malgre eux, 1994)

- Octavia Butler's Xenogenesis Trilogy

- Sheri S. Tepper's Beauty, Grass

- Joanna Russ's The Female Man

- Suzette Haden Elgin's Native

Tongue

- Charlotte Perkins Gilman's Herland

- Scott Westerfeld's Uglies shows a futuristic society

where one transforms greatly aesthetically at the age of 16, through

intense plastic surgery, to live in a society where all is peaceful and

beautiful.

- The Doctor Who episode "Utopia"

depicts the last of the human race in the future trying to find a safe

haven, but it is revealed in Last of the Time Lords that Utopia

was not as it was thought to be.

External links

- Thomas More's Utopia full text from Project Gutenberg (English

translation)

- Thomas More's Utopia the original

text from The Latin Library

- Utopia - The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2001

- Society for Utopian Studies - an

international, interdisciplinary association devoted to the study of

utopianism, with a particular emphasis on literary and experimental utopias.

- History of 15 Finnish utopian

settlements in Africa, the Americas, Asia, Australia and Europe.

- Towards Another Utopia of The City

Institute of Urban Design, Bremen, Germany

- Utopias - a learning resource from

the British Library

- Utopia and Utopianism - an academic

journal

- Utopia of the GOOD An essay on

Utopias and their nature.

Related terms

- Dystopia is a negative utopia: a totalitarian and

repressive world. Examples: Jack London's The Iron Heel, George Orwell's 1984; Aldous Huxley's Brave New World; Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451, Anthony Burgess's A Clockwork Orange; Alan Moore's V for Vendetta; Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale; Evgenii Zamiatin's We; Ayn Rand's Anthem; Samuel Butler's Erewhon; Chuck Palahniuk's Rant; Cormac McCarthy's The Road; Terry Gilliam's Brazil, Katsuhiro Otomo's Akira

- Eutopia is a positive utopia, different in that it

means "perfect" but not "fictional".

- Outopia derived from the Greek 'ou' for "no" and '-topos' for

"place," a fictional, this means unrealistic or directly

translated "Nothing, Nowhere" This is the other half from

Eutopia, and the two together combine to Utopia.

- Heterotopia, the "other place", with its real and

imagined possibilities (a mix of "utopian" escapism and turning

virtual possibilities into reality) — example: cyberspace. Samuel R. Delany's novel Trouble on Triton is subtitled An

Ambiguous Heterotopia to highlight that it is not strictly utopian

(though not dystopian). The novel offers several conflicting perspectives

on the concept of utopia.