Mircea Eliade: the sacred and the personal

-a prisoner of his time-

Luc Sala 2016

Beyond the academic contributions and publications that made his reputation the personal story of the Rumenian scholar Mircea Eliade, as revealed in the more recent (published or translated) biographical and autobiographical material has spawned a renewed interests in him. Does the appreciation of his work change if we look at his life from a different, more psychological perspective and try to discern and take into account the emotional drives and personality issues. What is there to learn from his history, what bearing had his emotional development, his struggle with life’s challlenges and inner tendencies, on his views? Can we relate his psychological issues to his work and attitudes, understand his dilemmas and choices better if we see him as confined by the temporality and historicity, the conditioning he himself saw as a core subject of Western and Eastern thought. This means going some steps beyond what Florin Turcanu in “Mircea Eliade. the prisoner of history”(2003) did and is more concerned with the defining experiences in his life than how this played out in his pre-war Rumenian time.

Trying to understand or even identify the influence of the psychological development of an author of course is not what Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault suggested, looking at the role and relevance of authorship to the meaning or interpretation of a text like in “the death of the author” (R.B). But can we separate, In the case of Eliade, the man and his work? His experiences and political stance in his youth have been such a shadow, over his reputation and in his personal life, that it makes sense to see where his work and life, in a dynamic and not static perspective (as evolving over time) mirror each other and especially how we can extract better his core message and meaning if we understand him as a person, as a product of his time and experiences.

I believe, that work and author are one, and that understanding Eliade’s work and its relevance will be facilitated by looking into the person he was, his development, traumas, epiphany and life scenario. He was one of the early bridges between the Hindu/Yoga world and the West and it is relevant to understand how he personallly dealt with the paradoxes, the secrets and the sacred of the East in translating it in Western academic texts, fiction and how the disclosure of biographical material can help here.

Looking at text, in a semiotic perspective, already links the

‘knower’ (here Eliade) to what he expresses and in

radical constructivism no objective reality is separated from human mental

activity. In this essay a further step is taken, can we understand Eliade and his work at a deeper level, following his

psychological processes, indentifying the different parts (self-states) of his

psyche and how he dealt with his expereinces. This of

course is a more speculative approach and in this essay follows a specific

understanding of the human psyche, but hopefully will yield insights that are

useful to understand Eliade in the context of his

personality, time and work.

This approach can be seen as a critical, even aggressive attempt to diminish Eliade’s importance. However, if we see it as a way to strip from Eliade all the ‘projections’and defence mechanism and to lay bare where his personality and self-states shaped his work and career, how he was a prisoner of his time and his nature, it may help to see him as the student of life he was, and less as the guru or saintly sage he was made.

Motivation

This essay is based on a personal interest, I feel a certain resonance with my own path In his quest for erudition, his wrestling with his sexuality, his reticense to let personal feelings show, his drive to publish and need for recognition, his experiences in India. So trying to understand Eliade means understanding myself. Mircea Eliade is no doubt an important factor in his field ‘the history of religion’, but before, studying ritual and especially the magical aspects of ritual I kind of discarded his notions concerning the then for me relevant fields like shamanism and the origin of ritual. His “Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy” (1951) focussed too much on Siberian roots, is less clear about psychedelic use and very encyclopedic and descriptive but without ‘presence’ and limits shamanism too much. The social, the magical, shyamanism is much more than a technology of ecstasy, so I prefer accounts from ‘insiders’. At that time, for me, writing about ritual, people like Stan Krippner and other anthropologist and ethnobotanists who really immersed themselves in the culture and world of their (more shamanic, ecstatic and magical than mystical and enstatic) subjects, seemed to me more relevant and were more open to the biological roots of ritual and their magical efficacy. With a lot more field experience and empirical work concerning the emotional roots of shamanism and ritual, they recognized more the biological factors, the physiological need for ritual, repetition, escape from stress and fear. He missed the biological and maybe even Wilson’s sociobiological, how we act (even in a ritual context) because of our biological and social situation, the evolutionary perspective.

He obviously was an expert and initiate in yoga and Hindu mysticism, but revealed little about the real workings and concentrated on ‘history’ in a very eruditeand broad, encyclopedic way. Some of his insights show up in his fictional work, but still more or less disguised. An example is in one of his short stories (the secret of Dr Honigsberger)where doctor Zerlendi, uses yoga to overcome the limits of time.

I found him somewhat arrogant like in his view that (only) historians of religion could elucidate the world about the secret significance of cultural creation; obviously he saw himself as well qualified, some passages in the ‘Portugese Diaries’ are less than humble. Eliade seemed to me more of an armchair anthropologist and philologist, an encyclopedist rather than an innovator, using mostly texts to base his ideas on and erudition, very publicly displayed and worn as a mask, as his life’s path.

In the context of ritual, shamanism, altered states of consciousness and the magical, Eliade’s approach, for me, was too much rationalizing the irrational, in line with what E. Kant, J. Fries and R. Otto did, in fact separating science and religion, with Eliade’s profane and sacred dichotomy as an epitome of this kind of thinking. This separation was welcomed in a time (historicity Eliade would have called it) when science seemed to finally cut to the core (relativity, quantum mechanics) and distance itself from religion, so separating the profane from the sacred was welcome. But even as Eliade noticed that in other, earlier times and other cultures the sacred and the profane were less separate, I doubt he realized that in another perspective there is not such a separation, that for instance ritual behavior is sacred and profane, has biological, psychological and social roots as well as magical aspects. In other words, his broadly accepted dichotomy was his (and his times’) projection, maybe a rationalization of the scale of inhuman war and suffering. He liked the universals, the grand designs, sometimes ignoring the reality on the ground. The lack in Eliade of fieldwork experience and immersion in the cosmology of the subjects (outside his yoga) is mentioned by others, but in this essay I will try to relate that to the psychological profile I try to sketch (much more is anyway impossible) of Eliade.

His ideas like the separation between ‘profane and sacred’ or ‘eternal return’, to me felt as based on a particular perspective, not really relevant for my research then, too much ‘his’ story. But in this essay I will look at them in a different context.

Methodology

This is not an essay in the literary critical tradition, but an attempt to look at Eliade in what could be called an holistic approach, seeing the man, his work, his time, his beliefs but above all his psychological matrix as a totality. This requires the use of one or more of the personality profiling approaches, like developed by Freud, Jung and in the science of psychology and psychiatry with Myers-Briggs (MBTI), BigFive or Enneagram. However, these systems don’t honor the multiple mask or subpersonality matrix that seems so evident in Eliade, where clearly different self-states are present and drive his actions and emotions. As an example, his burst of sexual energy are well recognized, even by himself. Here we will use the enneagram typology to mark the various self-states that emerge from the biographical material. Each self-state has its own drives and focus, and can be more or less dominant in a given situation, like at the time in the ashram. The enneagram system is widely used in psychotherapeutic circles, is not the only, but a practical way to identify personality tpes, even if it doesn’t recognize multiple self-states with each an enneagram type, as used in this analysis.

Eliade’s enneagram number (personality type) in his most common self-state (his normal ego-state) is most probably a number 5; introspected mind type, the investigator, engaged in books, libraries, details, obtaining knowledge. This kind of makes sense, he is nearly a quintessential type 5, these kind of people are described as the intense, cerebral type: Perceptive, Innovative, Secretive, and Isolated. According to the Enneagram Institute Fives are alert, insightful, and curious. They are able to concentrate and focus on developing complex ideas and skills. Independent, innovative, and inventive, they can also become preoccupied with their thoughts and imaginary constructs. They become detached, yet high-strung and intense.

Their motivation is to have everything figured out as a way of defending the self from threats from the environment. The Basic Fear of the 5 is being useless, helpless, or incapable and the Basic Desire: To be capable and competent. The 5 sees knowing as the most desirable, and in Eliade this is clearly knowing from texts and sources and using this to reframe the truth, a bit iconoclastic with aggressive statements or actions against any well-established status quo. Something we see in his pre-war Rumanian stance. The corresponding typology in the MBTI approach an INTP, INTJ, ISTP, INFJ or ISTJ, in Jungian terms: Introvert thinking.

There are however (and this is explained in more depth in my books about ritual, sacred journeys, festivalization) often other subpersonalities, ego-modalities or masks (different names for a self state) that emerge at certain times, triggered by memories or situations. These self states originate in traumatic situations, usually in the youth, where the only escape was to create a different mode of being, of dealing with the situation. These can be very negative experiences, but sometimes a mystical or epiphanic experience can create a new self state.

This situation with more ‘masks’ is what can explain some of the sometimes dramatic turns in Eliades life. There is in Eliade a 2 (helper) and 7 (magical child, hedonist, sexual, bodily experience) type of self state too and the inner child, his unconditioned true self in Easten perspective (essence) also seems to be a 2 (helper), this state is what one tries to reach in meditation and sometimes happens without obvious cause and is experienced as an epiphany, maybe this is what Eliade experienced in the drawing room in his youth.

Assigning these type numbers is based on analyzing his actions and his work, but also how he has memerized certain experiences. From his own recollections and observations in the biography and diaries his self-state at various time can be deducted with some probability, and certain mechanisms identified. During his ashram times, after a disappointing situation with his guru, he seems to have shifted to his number 7 modality, with ascetic exercises, yoga and eventuall tantric practice, not something a number 5 would engage in.

At other times, like when his first wife Nina was dying in Lissabon and he felt responsible for this because of an earlier abortion, the number 2 helper type emerged. Also in his novels and journals this more soft and helping tendencies showed, he was obviously trying to understand himself and his conditioning and in a way using his fictional writing to express another side of himself. Also his insistence to write in Rumanian, even in his Chicago days, indicates he realized this would bring him back to a specific mindset or selfstate he obviously regarded as precious. If ths really opened him up to his best and most creative side, or just helped him ignore his hidden tendencies remains unclear.

In general, Eliade was an enneagram number 5 personality but it were the deviations from this that may have formed him and have shaped his life. In this essay an attempt is made to relate his work to this personality and self-state profile. Profiling him, as is attempted here, is a peculiar process and with dangers of projection by the profiler (the author of this, me) but shows an alternative way to look at the relation between work and author. I do have considerable experience with this (see www.lucsala.nl/lucidity.htm) and explained and used the method in my other books, but the combination of psychological profiling and critical analysis is not very common.

Criticism

Understanding the somewhat complex psychological matrix of Eliade can help to understand the anomalies, and the choices he made in his work. In criticizing his work, I noted, the dynamics are often overlooked; Eliade was not an unchanging entity. He developed, learned, made mistakes, self-corrected, and different parts of his personality were prominent at different times. He was human, after all and inconsistency comes with that. His reputation, once Eliade was seen as the foremost historian of religion, has been waning, his youthful diversions and political positioning in pre-war Rumenia have tarnished his reputation, but didn’t those attacks force him to be even more precise and scrupulous in his later work.

Also his methodology is now criticized as dry, aiming at universals and lacking fieldwork reference for subjects outside the Indian context. He was thorough, but there is little spark in his work, it’s at times dry and even disorganized. But that is what an enneagram type 5 is, those types don’t flaunt emotionality, broaden rather than limit the scope of their work, don’t tell their innermost secrets, they know, that’s enough for them.

He hints at the deep impact of religious experience, but rather speaks of hierophanies than epiphanies. Heshows little of himself (in the scientific works), finds some emotional outlets and hints at what can be achieved with yoga in fiction, but never reaches the abundant praise of his ashram days and the spiriyuality there. His spirituality gradually becomes more of a mindset than a mystical peak.

His works are no doubt well researched, show great insights in the differences and homologues of the various religious movement, the root strands of yoga and Hindu/Vedic traditions, the shared focus on conditioning in Eastern and Western thinking, in how yoga aims to help one escape and liberate oneself from the maya , but seems to carefully steer away from the ecstatic, the sex, the altered states of consciousness he must have experienced in his ashram days. His more or less hidden self-state (the experience, enneagram 7) was awakened there, maybe he got in touch with his essence, but those were not so much about knowing as well as experiencing, in the mystical sense, beyond words.

Did he see that as sinful, trying to escape and hide this part of him, this lustful sexuality he could not really control at times, in a kind of Kierkegaardian self-constraint and guilt-trip? But he kept going, maybe repressing this inclination. In his Chicago days be became and acted as a guru, but in tackling esoteric subjects like shamanism, alchemy, witchcraft still showed his fascination. They all are much more adventurous and experiential, more ecstatic than the dry comparative religion stuff as expressed in the academic multivolume Encyclopedia of Religion (1987).

The danger of rationalizing the irrational is that the methodoly becomes irrational, driven by sentiments and Eliade obvious was driven by emotions, by the need to show his erudition, overcoming the sins of his youth, a Kierkegaard kind of fascination with salvation, sin, but shying away from the ethical root questions.

Eliade, who obviously had had a different kind of existential experience (being in the Shivananda Hindu ashram in 1931and exploring tantric sexuality on the side) recognized the sacred structures in much of what we do, but tended to rationalize this and relate this very much to the unconditioning tendencies in yoga and the structures and effects of myths, the religious, the symbolic.

When Eliade talks about the problem of the human condition, the temporality and historicity of the human being and conditioning at the center of western thought and preoccupied in Indian thought, it is a theoretical approach, a mental construct. It feels as if he projected his own experiences, deep yoga practice means immersion, deconditioning, freedom from the situation and maya, onto his subject matter. There is certainly denial, guild, he later deplores his excursions, his sexual drives, while at a deeper level they showed him the importance of the yogic practice.

The stamp and prison of historiality and temporality

Eliade very much identified with fate, again a Kierkengaard type of approach. His focus on historiality and temporality probably has some roots in Heidegger and Nietzsche, but isn’t it fascinating to see how he himself was a product of his own history and the times and places he lived in. How he evaded topics like ethics and morality, superficially as a rational observer, but maybe also in denial of his own struggle with his tendencies in his sub-personalities.

Eliade also seemed to have missed the importance of magic (or magical practice as in ritual) in religion and the very fundamental dichotomy between magical and anti-magical religions. He is aware of miraculous powers and the difference in how for instance siddhis (as in Patanjali’s yoga) are treated in Vedic and Buddhist perspective (the Buddhist is not supposed to show these to layman), but doesn’t treat this as a fundamental different way of perceiving the otherworld.

This is, I pose with some restraint, an oversight in Eliades historical perspective, in how religions and especially anti-magical reforms like Protestantism reformation, Buddhism and Sunni Islam developed and were at the root of iconoclasm and witchcraft suppression. This basic dichotomy in religious beliefs and practice seems very fundamental to me, and many of the religious wars were between magic and anti-magical factions, to this day. The distinction between the magical and the antimagical in the history of religions, the dichotomy between catholics and protestants, between sunnii and shia, between buddhists and Hinduists is what deserves attention if we want to understand what drives fundamentalist terrorism of our days. Buddha, Luther and the prophet Mohammed were obviously trying to strip the prevalent faith of all magical and supernatural powers, imagery and visualisations of the otherworld. Later developments have blurred this distinction, buddhist has moved from a strict and rule based 5th chakra religion to an amalgam with Bon and Hindu imagery and is now more of a 6th chakra religion. But such a classification of religions based on models like the chakra energy points is again something I miss in Eliade, .

The magical assumes a higher (hidden, true) self and the existence of an otherworld (the sacred), observed rituals and assume we have free will. The anti-magical religions kind of deny this, are more deterministic like the Calvinist stance or even deny the existence of such a self (Hindu ātmavāda versus the Buddhist anātmavāda).

The role of ritual

Eliade described, often in enormous detail, the various myths, rituals and practices in many traditions. The psychological and the social efficacy is acknowledged, but the magical somewhat denied. Having participated in many rituals the sacred, for me, is far more an emotional and body experience than a mind-trip, but Eliade kind of defined the sacred as a cognitive category.

It seems he shied away from what ecstatic or altered states of consciousness can bring and this is remarkable, seen his ashram experiences. Notably he more or less denoted ‘induced’ ectasy or the use of substances as second rate practices. But here, maybe because he saw his own experiences as sinful, he missed some important points. Others were less inhibited and did not deny the value and (pre-)historic importance of substance use. The philosopher and Vedic scholar Frits Staal looked into undogmatic (rational) mysticism and seemed to like psychedelics to explore that too. He pointed out that ritual existed before language (and meaning), and argued that syntax was influenced by ritual. He suggested that ritual behavior has animal roots and this has been widely recognized now (and the myths about animals in many cultures kind of support this). But if ritual (and this includes mantras according to Staal) precedes symbolic language and myth, and thus can be without meaning, then not all the sacred is based on hierophany (breakthroughs of the sacred, supernatural into the world) as Eliade posed. He didn’t see ritual as something we inherited from the animals. In his views about myth, symbol, religion and ritual those things were too easily grouped under the banner of the sacred. If rituals are biological, psychological and social but also magical (in reality or perceived) they are more than just sacred, they are cultural end evolutionary containers of ‘intelligence’.

Rituals, together with fire, were as I see them , instrumental in the human evolution, even more than the fairly recent (maybe 12-15.000 years old) symbolic language that is needed for myths. They were instrumental as a path towards specialization, hierarchy and the need to communicate and eventually self-consciousness. The historical development of play-ritual-law-religion seems absent in Eliade’s view of the sacred, his idea of balance was to return to the origin, not honoring evolutionary forces or the adaptation of beliefs to environmental factors or evolutionary trends.

Rational about the irrational sacred

So what did Eliade contribute really if we look at the deeper levels in his work. His basic approach, looking at religious texts and symbolism, feels a bit cold, cognitive, a rational look at the irrational. So what made Eliade see religion and the sacred as some fundamental, archetypical structure in the human mind, the only way we connect to the otherworld which in my view is way beyond the mind, but for the materialist is just an illusion?

Did he see the sacred as the source of self transformation, as the way to grow in consciousness, as the path to virtue, as the opposite of the ego building and deconnecting process of growing up, as the way to demolish the ego to reach a deep connectivity with all and everything. Or did he accept that the sacred for most is just an affirmation of their belief system, a sense of feeling at home and happy with what they are accustomed too. The choice between religion (or education, drugs, music, literature) as a tool to break the mask or to reinforce the mask? This is where Eliade (to me) shows his “Janus” face, he looks both ways, and doesn’t make a choice, where he shies away from being a guru and just exposes the two paths.

It has to do with what the Homo Religioso is. Is that the result of experiencing the sacred in a mystical moment? A process Eliade went through this several times, as his fascination with epiphany (see Lisbon Diary) and his appreciation of yoga and the ashram experience indicates. He described a stage in his youth as marked by an unrepeatable epiphany. Recalling his entrance into a drawing room that an "eerie iridescent light" (light as a quality of the sacred also fascinated him) had turned into "a fairy-tale palace":

“I practiced for many years

[the] exercise of recapturing that epiphanic moment,

and I would always find again the same plenitude. I would slip into it as into

a fragment of time devoid of duration—without beginning, middle, or end. During

my last years of lycée, when I struggled with

profound attacks of melancholy, I still

succeeded at times in returning to the golden green light of that afternoon.

[...] But even though the beatitude was the same, it was now impossible to bear

because it aggravated my sadness too much. By this time I knew the world to

which the drawing room belonged [...] was a world forever lost.”

He has thus experienced the otherworld at a very deep level in his youth and in the ashram (1931), but was his first epiphany (the drawing room oneness) maybe limited to a connection with the knowledge and wisdom in the books or material (art) around him? At times I have had such experiences, reading a book I became identified with the author, would feel rather than read the text, receiving more than just the superficial content, a hierophany in Eliade’s words. But I also had epiphanies dancing and drumming all night, unspeakable insights way beyond language. The ecstatic, like in the tantra encounters, are of a different kind and different intensity, and may have influenced Eliade much more, but then resulted in negation, in seeing it as sinful, as lust, nothing worth writing about in academic (rational) terms, just hinting at it in his diaries and works of fiction.

Perspective and complexes

Maybe it’s all a matter of perspective, and focus, and as he would say, of personal axis mundi.

For him that was language, specifically the Romanian language, he kept writing in his native language all his life, even living in Chicago and teaching in English. It seems this was his personal ritual, to approach the center in himself, although it may be, as I already hinted at, that this center was more an old stronghold to deny deeper tendencies. He valued knowledge above experience, or was it that he distrusted experience and ecstasy, being afraid of the irrational urges that could keep him away from his axis mundi, like his bursts of sexual manifestation. His confidence was a bit over par, maybe to hide his insecurity, haunted by a past where he let emotions and idealizations, identifications and political sentiment loose. Obviously he liked to be at the side of the superiority environment, but is this not a normal human tendency, entrenching oneself to hide the inferiority feelings. Covering an innate inferiority complex with the superiority of overwhelming knowledge and facts, constructing rather than proving universals, he in a way emulated somewhat the guru he saw and acknowledged in his Indian professor Dasgupta. But this was the man who kicked him out of his house because of a love-story (platonic) with his daughter.

So how much did Eliade bow to the perceived superiority in his life, how much integrity did he sacrifice in order to belong, be respected, and how can we see his alignment with the right wing Iron Guard in Rumenia in the thirties in that light? Was this no more than a ‘normal’ pattern, in those days many people embraced such a stance, and he just used his talents of expression to ‘word’ a general feeling that resonated with his own personality at the time.

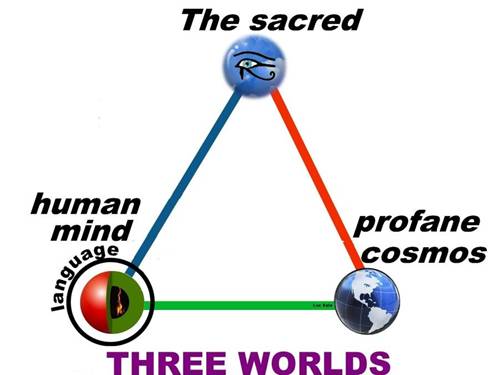

I believe that Eliade would agree with the simple three world diagram I use to show that inner world (human experience), outer world (cosmos) and the otherworld (sacred) are all connected. I have drawn a circle around the innerworld, for Eliade believed, like Lacan, that the world reve als itself to us humans as language and symbolism. He recognized the correspondences, the links between the human, natural and divine orders, but does not differentiate between the links between mind and sacred/divine and the natural and the sacred.

Here I miss in his work a model of the human psyche and how this archaic need to find an explanation, hence a religion, is related to psychological processes. That ‘ homo religiosus’ is based on a quest and need for authenticity sounds like an explanation, but how does this relate to meaning, what mechanisms make one look for the sacred? Is ecstasy the real driver, the attractor that makes us look for the otherworldy. The Enstatis, the contemplation of one’s own self, is only part of the work and following the practice and discipline of a ceratin tradition is hardly a guarantee for success, he himself took the high tantric road by night!

He obviously is aware that we are living within a ‘false’ and

conditioned self, as he mentions conditioning as the central problem of Western

and a preoccupation of India thought. He also describes yoga as a process of  unconditioning, what matters beyond

knowing the conditioning is to master them, burning them, yoga is then aiming

at very practical liberation of this burden of the ego. He does mention

processes like ‘regressus ad uterum’

(return to the womb) and death/rebirth experiences, and how we should try to

escape the temporality and historicity of the human being as we are being

immersed, situated, conditioned because

of that. We should, and he points at ritual and the sacred as the means to

escape the fetters of profane time, enter sacred time to become free. The illusion we live in, the maya that is all about becoming, not about being. Maye is about our conditioning, becoming in time and

history, suffering.

unconditioning, what matters beyond

knowing the conditioning is to master them, burning them, yoga is then aiming

at very practical liberation of this burden of the ego. He does mention

processes like ‘regressus ad uterum’

(return to the womb) and death/rebirth experiences, and how we should try to

escape the temporality and historicity of the human being as we are being

immersed, situated, conditioned because

of that. We should, and he points at ritual and the sacred as the means to

escape the fetters of profane time, enter sacred time to become free. The illusion we live in, the maya that is all about becoming, not about being. Maye is about our conditioning, becoming in time and

history, suffering.

In his interpretation of Buddhism however, where all models or ideas of the self are dismissed or deemed illusiory , I feel he didn’t see that beyond the initial approach in yoga, where on tries to escape the conditioning, there is a much deeper state, where the ego or personality is totally dissolved and no individual ego, soul or self-construct exists. This state, where the experiencer or observer is gone and only the observation remains, is way beyond what yoga normally brings, but in my view is what Buddhism hints at, hence the no-self.

Eliade saw religion as an archaic ontology, an explanation of existence that has deep roots. Eliade’s concept of the sacred and the profane is not to see them as opposites, but as ways to perceive the world or two alternate modes of being, maybe as dimensions but with the sacred as a hidden world, these days only perceived by ‘the connected’. A somewhat elitist approach, does not everybody feel the sacred, in their own way, as beauty, love, belonging, rightfulness, and does not everybody (including original man) at times pushes this away with materialistic rationalism. Don’t animals aim for beauty, balance, is all creation not an expression of the sacred? Eliade acknowledges the simultaneity of the worlds:

“By manifesting the sacred,

any object becomes something else, yet it continues to remain itself, for it

continues to participate in its surrounding cosmic milieu. A sacred stone remains

a stone; apparently (or, more precisely, from the profane point of view),

nothing distinguishes it from all other stones.”

All things and events exist in the material cosmos and the sacred, the Platonic Idea otherworld, but there subject to normal time and causality. There are links between the worlds, the notion of correspondences and sympathy allows partaking in the divine, not just perception. The sacred, I contend, is not only an inspiration or a view of the absolute, it is where change and causation resides.

Yoga, but not the practical side of it.

The books on yoga, starting with early essays in 1928, his dissertation in 1936-37, and extended and appended until 1954 and with many even more recent incarnations (like the one with an introduction by David Gordon White), have become classics, are very broad and deep, but stay at the encyclopedic and philosophical side, and are certainly not about the practice itself or the secrets and magical effects of yoga. Eliade undoubtedly immersed himself, with the help of one of the foremost scholars in the field, SurendranathDasgupta, in the sāmkhya yoga of Patanjali, attended a Kumb Mela in Allahabad, met Tagore, and experienced colonial India in the roaring twenties. However, some part of him, probably his adventurous selfstate looking for bodily experiences rather than intellectual escapism, entered the yogic life in an ashram. This after a hit with the moral (and catse/class) barriers of his times because of his ‘letter-exchanging’ love affair with Dasgupta’s daughter Maytreyi (who later published a rather different account than what Eliade put out in a fictional form). Renouncing the worldy however, and reaching real spiritual depth he also developed an interest in experiential and notable tantric yoga, he became a adept much beyond studying yoga as a philosophical concept. His repeated insistence on yoga as a path to not only to spiritual bliss and immortality beyond or outside profane time, but as a path towards freedom, in the now, in this body, hints at this. He describes it as being immersed in a spiritual experience way beyond what he knew from his youth, as much more than what his orthodox Christianity had given him. Part of this must have been his tantric night-life with a South-African dakini-sister a the Shivananda ashram. But some kind of guilt, labeling this ecstatic and epiphanic episode as sinful or at least not for general public consumption, prevented him from making this his path. Instead he went back to Rumenia, researched and studied even more about yoga and Indian philosophy, but also embraced a right wing stance. Again a superiority environment to cover his inferiority complex, like many of his fellow intellectuals of the time and with material benefits like a diplomatic post in England and later Portugal, but staining his post-war reputation.

There is no doubt that Eliade’s yoga has been influential, offers a good introduction in Indian thought and the history of yoga, but is limited in perspective, he obviously was influenced by the perspective of Dasgupta. His views on Buddhism and how Dravidian and non-Vedic yogas and philosophy play a role in the history of yoga can, also because of better access to sources these days, be critized. For me his treatment of the subject also reveals, in between the lines and in relation to biographical material, much about his psychological make-up, which helps to see him in historical context as someone who bowed, because of his reputation and guilt feelings, maybe a bit too much to convention, hid his real creativity and insights behind an overdose of erudition.

Sacred Space

The sharp distinction between the sacred and the profane is Eliade’s most noted theory, as I indicate elsewhere this nicely fitted with the separation between religion and science so obviously a major theme in the mid-twentieth century. The experience of the sacred in his view is an inner (religious) experience, but caused by external situations and impulses. He separates the ordinary, the biological, the rational from the divine, the otherworldly, but does so in a rather dogmatic way.

The Experience of Sacred Space makes possible

the "founding of the world": where the sac red Manifests itself in space, the real

unveils itself, the world comes into existence.

Now this approach fits with the times, the twentieth century of rationalization of the emotional. The sacred–profane dichotomy, but with a slightly sociological flavor, comes from Émile Durkheim, who considered it to be the central characteristic of religion:

"religion is a unified

system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things, that is to say,

things set apart and forbidden."

This, however, has roots in Durkheim’s fascination with taboos and group processes like ‘effervescence’ which he experienced as a child in the Jewish faith and the synagogue. Rudolf Otto in Das Heilige (Breslau 1917) also sees the sacred, the holy as the essence of all religions. The sacred or holy is at the same time fearful and fascinating and Otto used the word numinous to indicate holy, as the unknown, mysterious and yet powerful. Otto explained the numinous as a "non-rational, non-sensory experience or feeling whose primary and immediate object is outside the self", but according to Eliade this isolates the sacred.

Eliade sees the distinction in sacred and profane as universal, in his view traditional (religious) man distinguished the two basic levels of existence: the Sacred (divine, God, ancestors) and the profane world. To traditional man, things "acquire their reality, their identity, only to the extent of their participation in a transcendent reality". So something is only "real" if it conforms to the Sacred or the patterns established by the Sacred, the ideal. The rest is illusion.

There is profane space, and there is sacred space. Sacred space is space where the Sacred manifests itself; unlike profane space, sacred space has a sense of direction and it has, because of the appearance of the sacred, a center, a fixed point, an orientation.

When the

sacred manifests itself in any hierophany, there is

not only a break in the homogeneity of space; there is also a revelation of an

absolute reality, opposed to the nonreality of the

vast surrounding expanse. The

manifestation of the sacred ontologically founds the world. In the homogenous

and infinite expanse, in which no point of reference is possible and hence no

orientation can be established, the hierophany

reveals an absolute fixed point, a center. a

My problem with this is that for instance in ritual the two categories are not easily separated; is drinking coffee at the copy machine in an office every day at the same time not a ritual, and do people not attach magic significance to such rituals? And are there no cultures where there is no separation, where profane and sacred coincide, like for some Aboriginal people? The separation between the sacred and the profane fits very well in the mid-twentieth century separation between religion and science and maybe that resonance helped the broad acceptance of this idea. But did archaic or traditional man make this distinction or was it all the same, were profane and sacred not different? Were the pantheistic notions, that the divine is immanent in all and that all is sacred, not what motivated mystics and pagans alike? Is Eliades classification not very much in line with what science posed, before quantum-mechanics started to eat away at notions like existence, being, observation? These days the quantum-physicist not only dares to look at the role of consciousness, but is forced to do so because notions of linear time and objectivity are dwindling?

His approach, even as the subject itself is clearly non-rational, was to understand the technology of the sacred, with an emphasis on time and symbolism. As an historian that makes sense, but he has in a way become a prisoner of the same time he rejects, historical time. Sacred time in essence is beyond time, beyond causality, beyond entropy, and is closer to information and consciousness, to chi, love and eternity than clock-time.

Eliade pointed at the separation between the sacred and the profane, but in a way idealizing the days that these two aspects of life were still one, the times where the sacred was still the bedding of life, not a separate thing for Sunday services. Modern life lost this connection, even as it retains the link with the myths and the sacred structures in many ways, our world, our institutions, buildings and rituals are still a mirror of what we perceive as the sacred blueprint that gives meaning to life.

The inversion of meaning, by experiencing the sacred in daily life,may have been an incentive to identify and separate the sacred and the profane. He had experienced the direct awareness of an otherworld, his epiphany and tantric practice, and tried to go back to that mystical state, to remember how it felt. A cognitive dissonance of sorts, and maybe he believed that by understanding more of the sacred, he could get there. But his life taught him, that only in adverse conditions, like Job, he would open the doors to the truly religious experience, but he did his best to recognize this in others.

Based on his experiences, he could not ignore the sacred, or see it, as materialists like Daniel Dennet, label it as a result of a biological process, a distortion of our picture of reality, an illusion created by our cognitive apparatus, pareidolia.

Man becomes aware of the sacred because it

manifests itself, shows itself, as something wholly different from the profane. To designate the act of

manifestation of the sacred, we have proposed the term hierophany.

It is a fitting term, because it does not imply anything further; it expresses

no more than is implicit in its etymological content, i.e., that something sacred

shows itself to us. It could be said that the history of religions —

from the most primitive to the most highly developed — is constituted by a

great number of hierophanies, by manifestations of

sacred realities. From the most elementary hierophany

— e.g. manifestation of the sacred in some ordinary object, a stone or a tree —

to the supreme hierophany (which, for a Christian, is

the incarnation of God in Jesus Christ) there is no solution of continuity. In each case we are confronted by the same

mysterious act — the manifestation of something of a wholly different order, a

reality that does not belong to our world, in objects that are an integral part

of our natural "profane" world.

in ‘The Sacred and the

Profane : The Nature of Religion: The Significance of Religious Myth,

Symbolism, and Ritual within Life and Culture’

(1961)

Sacred time and out of time

“In

imitating the exemplary acts of a god or of a mythic hero or simply by

recounting their adventures, the man of an archaic society detaches himself

from profane time and magically re-enters the Great Time, the sacred time. “

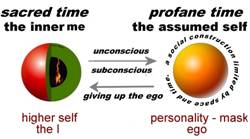

Eliade distinguishes profane time and sacred time, and there is some resonance in this with the (subjective but real) time of the fundamental self and the objective but illusionary (clock) time of the spatial and social representation of the self we declared as real in physics, of Henri Bergson. I like to model this as a distinction between two self-states. The sacred time is what we experience in the most inner self, while in our assumed self (ego-states) we live in clock-time, seemingly real but according to esoteric insights with which Eliade aligns, an illusion (maya).

In the sacred time state, and I believe this should include states of consciousness like psychedelics, lucid dreaming and creative (inspired) mindstates, we experience the illusion or at least the flexibility of time and space. But does this mean that such states always refer to mythic stories and return to archaic times? Are such sacred journeys in themselves mythical?

According to Eliade:

“myths describe … breakthroughs

of the sacred (or the ‘supernatural’) into the World".

If he does mean rituals, even if limited to mystical enactments, are ways to lure or bring man into this special state where one can give up the constraints posed by our ego-attachment to time and space, duration, quantity and causality, I do agree. However, to see ritual as exclusively going back to the mythical age, the time when the Sacred entered our world, giving it form and meaning as Eliade does

"The manifestation of

the sacred ontologically founds the world"

and equating the mythical age with sacred time, the only time that has value for traditional man, ignores those other states. It brings in the notion of history, something of the past, fitting with the eternal return ideas of Eliade, but still time-bound. I believe this state is esentially free from ‘normal’ time and causality, one can wander anywhere, in the heavens, hell, the past or the future.

This brings me to what psychedelics have learned me, that there are states of mind where this wandering in any otherworld is possible, but where the sacred is only one of the realities, where the archetypical imagery is certainly a factor but doesn’t need to be based on imprints from the past but can emerge from beyond time (including the future), where will and freedom cooperate and where the magical and the mystical, the active and the receiving unite.

It is assumed that Eliade has had some psychedelic experiences, but obviously he rates them less than the ‘true’ mystical state, in line with what yogis and meditation teachers claim. This is maybe the root for his moralistic distinction between ‘easy’ and ‘difficult’, between salvation, liberation (moksha) or revelation by grace, faith or drugs versus good works, a practice and discipline.

The far more engaging and exploring anthropologists like Stan Krippner and recently Jeremy Narby seem to have better grasped the width and relevance of psychedelic inspiration for belief systems and religions. Set and setting of psychedelic experiences make all the difference, the “Good Friday” experiments in a more or less traditional Western setting are quite different from the Ayahuasca or Iboga rituals experienced by more recent researchers of the otherworlds and innerworlds. The essence of time, or getting beyond or outside time seems to be a major factor.

Eliade seems to have been operating within a paradigm or from personal experiences where time still wasn’t totally gone, hence his perception of the cyclical, the eternal return to the origin. He expanded the model and recognized how many cultures dis the same, but didn’t see that even ideal or heavenly models are but a subset of worldviews. If Eliade claims:

"For archaic man,

reality is a function of the imitation of a celestial archetype”,

he limits the impact of what his ‘sacred state’ can also bring. Not only the understanding of the Hermetic “above as below”, but the realisation that the two (or many) are one, and that reality creation (the magical) starts at that level.

In Eliade’s view, the mythical age was the time when reality (manifestation) started and the Sacred appeared, the beginning, in illo tempore. He argues that for the traditional man, a kind of ideal we should maybe not aspire to be but can learn from, only the Sacred and only the beginning of the Sacred, the mythical era of the Gods and heros has value.

"primitive man was interested only in the

beginnings … to him it mattered little what had happened to himself, or to

others like him, in more or less distant times".

Through the vehicles of ritual and myth going back to the beginning, repeating and imitating (and thus reviving and reliving) the most distant past to find value for the present. A nostalgic vision, the noble savage reinstated as the original, the holy, something we need to study, as Eliade suggested somewhat authoritarian, from the perspective of comparative religion in historical context. That perspective he made universal, there are laws and mechanisms that he claimed apply broadly, too broadly as some critics remarked, citing cultures and belief systems that don’t follow Eliade’s rules.

That most rituals don’t really go back to the archaic begining, just to a beginning of a specific tradition, like the Catholic rituals to the days of Christ, doesn’t seem to bother him much. He likes the repetition, the cyclic view of time, as it supports his eternal return. There is a kind of obsession with what profanely could be called ‘time travel’, but to extend this to time travel to a (then influenced in a complex feedback loop) future, honoring prophesy as a valid and real phenomenon as most religions do, goes too far (except In his fiction).

That change, innovation, initiative and cultural mobility could result just from this capability to step outside time, that causation is maybe just anticipation of a future, that evolution is remembering the future, that time is indeed illusion, this eludes him. He just points out that the eternal return has not stifled progress or immobilized culture, and suggests it stimulates to re-enact the heroic voyages and great endeavour of the mythical era. Maybe true for suicide bomber terrorists, but is that why Einstein came up with relativity? Is science a mythical journey, or as I believe a fishing expedition into the ultimate reality we feel is out there?

Eliade himself notes that the idea of only linear, historical time is one of the reasons for modern man’s anxiety (The Terror of History) , but spends his career honoring that historical perspective. He feeds the importance of time, by splitting it in profane and sacred time, but doesn’t discard time as part of the maya, the illusion. Is the eternal return to archaic mythical time not a preoccupation, a mechanism to escape the oppressing notions of fate and death, find some stimulation and encouragement to go on, like these days we like to read science-fiction or use drugs, alcohol and internet? Eliade accepts the desire of traditional man to escape the horror of historical time and certain death, but doesn’t see that the return to the mythical time is maybe just as artificial and limited as our escape into materialism. Here I feel that his criticism of Marxism,which sees religion as the ópium of the people’ and as a form of protest by the working classes against their poor economic conditions and their alienation, has to do with this. He was in essence a defender of the Faith, any Faith, and looking at the eternal return as a fear based escape didn’t really fit that position.

Eliade and witchcraft, astrology:

Obviously Eliade could not ignore the more esoteric aspects of religion, like the magical. “Contemporray scholarship has disclosed the consistent religious meaning and the cultural function of a great number of occult practices, beliefs and theories.”

He was not really fond of magic and witchcraft, even as he is impressed by the amazing popularity of witchcraft as he writes: “the contemporary interest in witchcraft is only part and parcel of a larger trend, namely, the vogue of the occult and the esoteric – from astrology and pseudospiritualist movements to hermetism, alchemy, Zen, Yoga, Tantrism and other Oriental gnoses and techniques.” and concerning astrology, he is amazed at the craze for astrology in view of the limited scientific research into the history of astrology. He speaks about astrology as ”the hope one can know the future” but also points out is incompatible, even a defeat of Christianity. He admits that it has a “parareligious dimension, considered superior to the existing religions because it does not imply any of the difficult theological problems: …” It makes one feel in harmony with the universe.

He mentions (in Occultism, Witchcraft, and Cultural Fashions: Essays

in Comparative Religion) the existence

of magical schools, groups that practice ceremonial magic, but sees the

information about them as scarce and suspect, magicoreligious

cults are not what Eliade seems to go for. He doesn’t deny the existence of witchcraft

and the deep historical and religious roots, but follows more or less the

general understanding, including blaming the Church and the Inquisition for the

witchcraft hunts, ignoring that it were the clearly anti-magical protestants

who burned the most witches.

Eliade and symbolism, correspondences

‘Religious symbolism discloses divinity and expresses archetypical divine

structures’

and recognizing its function as a

kind of language to connect to the sacred seems to be a straightforward approach, but ignores to some degree

A: the biological roots of certain

symbols (phallic, triad, sun) based on repetition, visual patterns and

similarities.

B: the idea of ‘correspondence’ and

‘sympathy’, the resonance between the inner, outer and otherworld that is so

much at the basis of magical understanding and ritual practice.

Eliade sees (religious) symbols as

pointing to something real, beyond beyond being a

replica of objective reality, they are a revelation of the sacred, as hierophanies, his word for contacts between the sacred and

the profane. Eliade sees (1961)

“the multiple variants of the same complexes of symbols … as endless

successions of ‘forms’which, on a different level of

dream, ritual, theology, mysticism, metaphisics etc.

are trying to ‘realize’the archetype.”

This meaning may have been lost in

modernity and rational secularity, but the original link to the sacred is still

there, pointing towards transcendence.

“The World ‘speaks’ in symbols,

‘reveals’ itself through them”

at a more profound, mysterious

level, often layered and mulivalenced, than everyday

experience. Again, these multiple and sometimes paradoxical levels of meaning

are what in traditional magic texts, going back to very old understanding like

in the Vedas, is referred to as ‘correspondences’ and knowing the

correspondences (Ya evam veda) defined the power of the priest, Brahman, magician. Eliade kind of acknowledges that he who deciphers the

meaning of symbols will find existential revelations, but doesn’t translate

this in (magical) power. He admits, based on his idea

of the value of theoriginal beginning, that in the

archaic perspective the power of a thing resides in its origin, "knowing

the origin of an object, an animal, a plant, and so on is equivalent to

acquiring a magical power over them", but this is only part of the notion

of a correspondence. I suggest that making a distinction between a virtual

correspondence (in our mind, using our intuition and imagination) and a outerworld correspondence like a physical resonance

(similarity) would help to understand the idea of sacred space and magic.

Symbols are both innerworld and outerworld

phenomena, even as language is more of an innerworld

(see diagram above) thing.

The reality of for instance ‘sacred space’ is in Eliade’s view a mostly symbolic, not a realistic physicality with ‘hard’effects on the outcome and progress of a ritual. Space is not homogenous for a religious man, there are qualitative differences (and a center), and sacred space in his view is symbolized space. This is maybe clear for man-made sacred spaces, but what about power spots in nature? These sometimes also have symbolic meaning like that places for temples and shrines are often chosen because there is something symbolic around, but how symbolic is the biodiversity often present in such ‘power spots’, and what about ley-lines and other measurable and hardly symbolic energy indicators? It may well be that such places represent some kind of symbolic order in the universe and obviously attract people, but to see such places as displaying the universe and specifically pointing at the center, the origin, the vital interchange point between the divine and the human planes, the sacred and the profane and brings people back to experiencing paradise and timeless (eternal) return to the original (mythical) state (the moment of creation, sacred time) is stretching it a bit. Or should we deduce from this that the biodiversity of such a sacred place is proof that even the plants and the animals long for such an experience.

As I have explained in my book ‘Ritual’ (2014) I believe rituals (including prayer, yoga, festivals) offer the possibility to enter a state of consciousness that allows us to enter the sacred (hierophanic in Eliade’s idiom) space and time, or in other words escape the limitations of space and time, enter cosmic space and time, but also allows for influencing ‘normal’ reality (the magical aspect of ritual), see and feel the beyond.

Conclusion

Mircea Eliade

can be defined as always looking for knowledge, an encyclopedic searcher for

universals, but judging him or his work as separate from his psyche and

personal history doesn’t do him right. He obviously was not an easy man, he had

complex layers or self-states that would emerge in certain situations. He was,

like all humans, not a constant, but shows development in his views and

attitude, and his work and actions reflect this development, his internal

struggles and his ways of repressing certain parts of his psyche and associated

memories. These situations and his attitudes and drives can be deducted from

the available material; notably the periods in the ashram and around and after

the death of his wife show a somewhat different Eliade.

To describe Eliade as wistfully melancholic longing and also in denial of his

sexuality (Jon Bartley Stewart) may

be true in general, but there were moments and periods, that another Eliade emerged. His too obvious denial of this and most of

his emotions in his work only underline how important these events were. The

focus on his pre-war Rumanian activities as defining him is therefore not

justified, his actions then were in line with his psychological growth towards

maturity, the underlying themes of lust (seeking the tantric extremes),

mystical epiphany, helping and guilt (ethics) that impacted so much (as in not

dealing with them) his work are more important in understanding his choice and

approach of the subjects he did address. He makes knowledge or even truth a divine

quality, but seems to miss or rather

consciously evade the link to action. He obviously had very mystical

experiences, but this doesn’t shine through in his subsequent dissertation and

books about yoga, but comes back in some of his fictional works and his

journals.

If we want to understand Eliade and his work, we thus have to look at his psychological profiles, not only the obvious one of him as a dedicated knowledge worker and encyclopedist of religious movements, but also his more hidden sides, his complexes and guilt feelings, and this essay is an attempt to do so, from a specific and maybe personal perspective. Above all we should see his life as a process, as a journey of self discovery, of slowly reaching a goal that he himself pictured as a ‘center’. Then Eliade emerges as a man living the myth of uncovering his conditioning that he so aptly recognized in the religions in the world.

These thirty years, and more, that I've spent among exotic, barbaric, indomitable gods and goddesses, nourished on myths, obsessed by symbols, nursed and bewitched by so many images which have come down to me from those submerged worlds, today seem to me to be the stages of a long initiation. Each one of these divine figures, each of these myths or symbols, is connected to a danger that was confronted and overcome. How many times I was almost lost, gone astray in this labyrinth where I risked being killed... These were not only bits of knowledge acquired slowly and leisurely in books, but so many encounters, confrontations, and temptations. I realize perfectly well now all the dangers I skirted during this long quest, and, in the first place, the risk of forgetting that I had a goal... that I wanted to reach a "center".

Journal entry (10 November 1959) published in No Souvenirs (1977) , 74-5. Journal II, 1957-1969 (1989).

Literature

Works by Mircea Eliade; many more than this small selection

Novel of the Nearsighted Adolescent).

The myth of the eternal return, or cosmos and history

The Sacred and the Profane : The Nature of Religion: The Significance of Religious Myth, Symbolism, and Ritual within Life and Culture

Journey East, Journey West, autobiography 1907-1937

Patterns in Comparative Religion

Myth, Religion, and History, geredigeerd door Nicolae Babuts

Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy

The Forge and the Crucible

Occultism, Witchcraft, and Cultural Fashions: Essays in Comparative Religion

In 1987 the multivolume Encyclopedia of Religion

JOURNAL I 1945 - 1955

JOURNAL III: 1970 - 1978

JOURNAL IV: 1979 – 1985

NO SOUVENIRS: JOURNAL, 1957-1969

About Eliade and/or quoted

Roland Barthes: "Death of the Author" (1968) "it is language which speaks, not the author".

Michel Foucault "What is an author?" (1969)

Staal, Frits (J.F) Exploring Mysticism 1975 and Rules Without Meaning: Ritual, Mantras and the Human Sciences 1989

Rudolf Otto: Indiens Gnadenreligion 1930

Jon Bartley Stewart; Kierkegaard's Influence on the Social Science

Florin Turcanu 2003 “Mircea Eliade. the prisoner of history)

Bryan Rennie; Changing Religious Worlds: The Meaning and End of Mircea Eliade

Cristina Scarlat (edit), Eliade once again 2011

Mihaela Gligor, OPINII on MIRCEA ELIADE,

John Daniel Dadosky; The Structure of Religious Knowing : Encountering the Sacred in Eliade and Lonergan (2004)

Ion Zainea , The World War II and Europe's destiny in the notes of the journal from Portugal of Mircea Eliade (1941-1945)

Books by Luc Sala (free downloads)

see www.lucsala.nl for articles etc. and the mindlifttv channel on youtube.

www.lucsala.nl/festivalization.pdf

www.share-shop.nl/sacredjourneys.pdf

and many books in Dutch.